Snake

Introduction

Our sincere thanks to the Canadian Herpetological Society and BC Reptiles & Amphibians for the important work they do.

British Columbia is home to nine species of snake. B.C.’s northwest-southeast alignment of mountains and valleys creates unique environments, from the warm and wet southwestern valleys and coastal areas to the warm but drier interior valleys and ranges.

The southern interior valleys are home to six snake species and these include the Western Rattlesnake, sometimes referred to as the Northern Pacific Rattlesnake, which is the only poisonous snake in B.C. The Western Rattlesnake population in B.C. is “small and confined to dry grasslands in Bunchgrass, Ponderosa Pine zones of Okanagan-Similkameen, Thompson, Nicola and Kettle valleys, as well as the Lytton-Lillooet portion of the Fraser Canyon.”

The Sunshine Coast is home to four species and we narrow our focus on these as they are the snakes that we are most likely to encounter around Hotel Lake. First we will discuss how to recognize each snake and follow that with a more general explanation of their lifestyle and activities.

The four snakes in our midst include:

Common Gartersnake (Thamnophis sirtalis),

Western Terrestrial Gartersnake (Thamnophis elegans),

Northwestern Gartersnake (Thamnophis ordinoides),

Northern Rubber Boa (Charina bottae).

Note: The Sharp-tailed snake is a small rare snake found on south Vancouver Island and possibly inland but, to date, has not been reported on the Sunshine Coast.

Common Gartersnake

Common Gartersnake

This snake is the largest gartersnake ranging from 46 - 130 cm. Males are generally smaller than females. They have large heads and prominent eyes with large round pupils. Their body is black or grey-green with a yellow-green dorsal stripe (stripe running down the snake's back) and red barring on the sides and lateral stripes (stripes running along the snakes sides) below. The belly may be pale yellow or darker tones, even black but the chin and neck will display the lightest colour. Seven yellow upper labial scales (scales along the upper "lip" of the mouth) can be used to identify this species.

Western Terrestrial Gartersnake

Western Terrestrial Gartersnake

This snake is between 15-75 cm in length with females growing larger than males. They have strongly keeled (centre ridged) scales, a large head and large eyes with round pupils. They have two distinct colour variations: a darker coastal, and a lighter interior variation. The coastal variation of the WTG has dark brown-black body colour with an orange-yellow dorsal stripe and two yellow lateral stripes. The pale belly may have darker blotching or markings. Both types typically have a dorsal stripe and two lateral stripes.

It can be differentiated from the other gartersnake species in British Columbia by it's 8 upper labial scales.

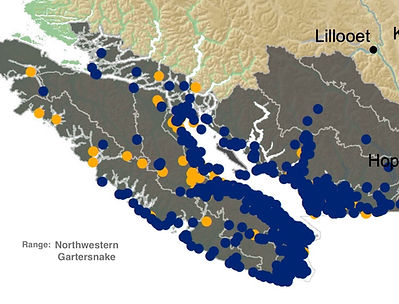

Northwestern Gartersnake

Northwestern Gartersnake

This is the smallest gartersnake in B.C., ranging in length from 35 – 60 cm, with a few exceptional individuals reaching 75 cm. Males are typically smaller than females. Northwestern gartersnake colourations vary considerably. Most individuals are a dull brown-grey to olive, often with faint checkering on the dorsal surface and dorsal stripe. Albino and Melanistic (rare condition where the snakes coloration is extremely dark or even black) populations occur. The dorsal stripe, if it is present, may vary in width and may be bright yellow, red, tan, blue, white, or cream. The scales of the dorsal surface are highly keeled. The belly is usually pale, and some individuals will have bold red or black markings. These snakes can be identified by their 7 upper labial scales.

Northern Rubber Boa

The Northern Rubber Boa

The Northern Rubber Boa is a thick-bodied, but small snake that is almost always less than 70 cm long. Females are larger and may reach 80 cm. They have loose skin with very small smooth body scales that give it a rubbery appearance and a uniform colouration; this can be olive green, chocolate or mocha-brown and all have a yellowish belly. The head and tail are similarly blunt in shape, making them difficult to differentiate and earning them the nickname: “Two Headed Snake”. The eyes are very small and have vertical pupils. Juvenile Rubber Boas are very small and more pink/orange in colour, semi-transparent and closely resemble a large earthworm.

Rubber Boas are referred to as ancient or primitive, in part, because they have a pelvic girdle near the cloaca (area where waste is collected before being passed to the vent) and, in males, small dark bony projections (spurs) are discernible, the evolutionary remnants of hind limbs.

______________________________

Having introduced the four local snakes we continue with a more general overview of their characteristics and lifestyle.

A Few General Characteristics

A snake’s body is covered with scales which provide protection, great flexibility and minimize water loss in hot-dry weather. Snakes regularly shed their skin, usually as a single piece, in a process called ecdysis.

Snakes do not have eyelids. Instead, a clear scale covers each eye providing protection. Snakes have poor hearing because they do not have external ear openings.

Using smell as their primary sense, snakes navigate the environment to find mates, locate familiar habitats and to hunt prey. Scent molecules are detected primarily by their forked tongue, which is flicked in and out of the mouth. The snake can distinguish the relative concentration of airborne scents on either side of its tongue thus providing a highly accurate sense of the direction of the source.

Here is a lovely short video from Northwestern Gartersnake Reptiles of BC.

Locomotion

Snakes use a variety of techniques to move both on land and in the water. The four primary methods of locomotion on land are:

Concertina: In tight spaces where movements are limited, snakes can move like an inchworm does by pushing it’s head forward then, clutching the ground with its chin, it arches its body and then pushes its head forward again.

Rectilinear: The snake keeps its body straight and creeps straight forward rather slowly using its scales to push itself forward.

Serpentine: This motion begins with the snake pushing away from a fixed object and then, undulating its body, it uses its belly scales to maintain momentum forward.

Sidewinding: When on smooth surfaces like sand or mud they throw their head forward and wriggle their body so that it follows, and by repeating that cycle they move forward.

Swimming: Snakes may use any combination of body motions to swim on the surface. They do not have gills but have lungs. Gartersnakes can stay submerged for 15-20 minutes. They can also drown if they are prevented from reaching the water surface.

Breathing (nostrils and glottis)

Snakes breath through their nostrils. An additional opening, called the glottis, is located in the bottom of their mouths just behind the tongue. The glottis is normally closed, but when opened to intake air it is connected to the trachea (windpipe), bronchus and lung. When a snake is in the process of swallowing prey, its glottis can reposition off to the side of it's mouth so that the swallowing of prey does not prevent the snake from breathing.

A small piece of cartilage inside the glottis vibrates when the snake forcefully exhales. This creates the characteristic warning hiss that a snake makes when it senses an approaching predator, be it animal or human. The hiss can be translated to mean, leave me alone.

Snakes have two lungs but only the right lung is fully functional with the right bronchus terminating in the right lung. In most snakes the short left bronchus terminates in a vestigial, or rudimentary, left lung. The size and functional capacity of the left lung varies depending on the species; for example, in some water snakes the left lung is more functional because it is used for hydrostatic or buoyancy purposes.

Body Temperature Regulation

Snakes are cold-blooded and their body temperature changes with the ambient conditions. In cold weather they become sluggish. Snakes can increase their body temperature by lying in the sun to warm up. To survive cold winters, snakes look for an underground cavity or den to escape and insulate themselves from freezing temperatures. They also stop eating and their metabolism slows down and they enter a “hibernation-like” state known as brumation. As the “range maps” (above) show, there is a limit to how far north snakes can survive in Canada. It is our cold winters that limit snake habitat. Remarkably the Common Gartersnake can be found near Fort Smith, NWT, further north than any other snake in North America.

In very cold conditions there are few sites available to avoid subfreezing temperatures. Common Gartersnakes, for example, may commute several kilometres to communal brumation sites where their numbers may reach into the thousands. Here on the Sunshine Coast, winter conditions are relatively mild and there is plenty of denning habitat so snakes may den alone or in small groups.

The Northern Rubber Boa requires more insulating properties in their den habitat such as soils loose enough for burrowing, rodent holes, leaf litter, rotting logs and stumps.

Life Cycle

Gartersnakes, depending on the species, may live between 10 - 20 years. The Northern Rubber Boa is believed to live, some sources suggest, up to 20 years.

During their lifetime, snakes repeatedly shed their old skin, a process called, ecdysis. This can happen several times a year while the juvenile snake is growing but less often in adulthood. Approaching ecdysis, the snake’s colouration will become dull, and its eyes will glaze over.

Snakes are often seen basking in the sun on wood piles, stone walls, hedges, and rocks. In particular, pregnant females warm themselves to raise their body temperature and accelerate fetus development.

Gartersnakes do not mate until two years old. Mating occurs in March or April after emerging from winter dens. This is also a time that groupings of these snakes may occur which, until now, were thought to be brief mating events. However, research has recently documented that the social interactions and gathering tendencies of gartersnakes are likely more complex and meaningful than our previous understandings.

All four snakes in our area are ovoviviparous meaning that they do not lay eggs but rather give birth to fully developed young who immediately venture off alone and receive no parental care. Details below:

Common Gartersnakes give birth to 10-15 newborn between 14-22 cm in length.

Western Terrestrial Gartersnakes give birth to 3-24 newborn between 12-22 cm in length in a variety of patterns such as solid coloured, checkered or striped.

Northwestern Gartersnakes are not fully studied but believed to give birth to 3-20 newborn between 11-15 cm in length.

Quite differently from gartersnakes, the female Northern Rubber Boa reaches sexual maturity after 4-5 years. Mating occurs in the spring after emerging from hibernation. The female gives birth to only 2-8 young in late summer every two years. The 4-5 year delay in attaining maturity and the small number of young every two years is countered by a 20 year life span during which the female may be successful in adding significantly to the overall population.

Habitat

Snake habitats include underground burrows, trees (semi-arboreal) and fresh and salt water. These habitats include forest clearings and edges, fields, wetlands, the shorelines of lakes or rivers, rock outcrops, and mountain slopes. Snakes will also be encountered near ecotone areas where one type of habitat meets another such as the edges of forests or fields and the marshy edges of wetlands and lakes. The prey that snakes feed on tend to concentrate near trail edges and human-excavated areas where sand and gravel materials are removed and this attracts snakes accordingly.

When the weather is cool, snakes attend open areas where they can bask in the sun and maintain optimal body temperatures. During cold winters, snakes must avoid freezing by hibernating in dens, usually underground, in rock crevices, burrows, root hollows or other thermally-sheltering habitats below the frost line. Here on the Sunshine Coast where winters are relatively mild and denning habitat is readily available, gartersnakes may hibernate alone or in small groups.

The small and smooth skinned Northern Rubber Boas will occupy a variety of ground habitats and cover, generally preferring more humid areas and avoiding hot dry areas. They spend much of their lives either concealed or underground. Depending on seasonal temperatures, they can be active during temperate weather but on hot dry days, may switch to nocturnal foraging.

Foraging and Diet

Snakes eat their prey alive and whole. They can swallow prey much larger than their head because of their elastic skin and numerous joints in the skull and elastic ligament that permit independent movement of upper and lower jaws. They grab food and feed it down with teeth curved to the rear. The process of swallowing prey can be lengthy so they resort to breathing through a moveable windpipe opening called the glottis.

Snakes are opportunistic by nature. Our west coast snake habitats, include deciduous forests, fields, wetlands, streams, lake and river edges and tall grasslands, all of which are thriving with suitable prey. While snakes hunt primarily during daytime, night hunting is certainly possible.

Local newborn gartersnakes, are between 14-22 cm in length, fully independent and they begin foraging for earthworms and very small frogs. Adults hunt anything they can catch and swallow such as frogs, salamanders, tadpoles and toads and they also feed on a variety of small animals such as mice, nesting birds, small snakes, slugs, snails, earthworms, sowbugs, millipedes, insects, and spiders. In water they pursue small fish, leeches, crayfish and aquatic insects.

Common Gartersnakes also prey successfully on “toxic” Rough-Skinned Newts and “poisonous” Western Toads although the snake may suffer subsequent sluggishness and appear dazed.

The Western Terrestrial Gartersnake is known to regularly forage intertidal areas and even swim between coastal islands. Accordingly, it has the most varied diet of any snake in British Columbia. In coastal areas, they mainly eat fish, both freshwater and saltwater. In other areas, they commonly forage for all the usual prey, even other snakes. They are known to have a unique hunting technique in which they coil around the prey and constrict it, while biting and chewing. Their saliva glands secrete a mild toxin that relaxes the prey for swallowing.

Smallest of the three gartersnakes is the Northwestern Gartersnake which forages in daytime and is described as being “lazier” than the other gartersnake species. They hunt slugs, earthworms, snails, and small amphibians and are particularly fond of eggs of any kind. They are often found near aquatic habitats in areas that are densely vegetated like meadows, forest edges, estuaries, and beaches, but they seldom enter the water.

Threat to Humans?

Eight of B.C.'s snakes are completely harmless.

All snakes found on the Sunshine Coast, at the time of this writing, are considered to be non-venomous and harmless to humans. The reality is that snakes are only a threat to the worms, frogs, mice, fish and insects they feed on.

Northern Rubber Boas are known to be very slow moving and never strike at or bite humans under any circumstances, however they will release a potent musk from their vent if they feel threatened.

Western Terrestrial Gartersnakes do have a “mildly venomous saliva” that can cause muscle infection which may cause pain and swelling.

How can Humans Help and Respect?

Snakes have a biological history that originates in the Jurassic period, some 150 million years ago, but in our brief history on Earth, we humans have still not assembled a complete researched based understanding of snake evolution. Instead we have allowed mysteries, myths and the sometimes-legitimate fears of venomous snake species to drive our perceptions. Worldwide, snakes are often hated, feared and many are killed sometimes for no good reason.

The worldwide populations of snakes is reported to be in decline and the primary causes are:

habitat destruction from human developments,

persecution,

roadkill, associated with human developments.

Here in British Columbia, all snakes are protected under B.C.'s Wildlife Act. It is illegal, in B.C., to kill, harm, or remove snakes from the wild.

With no poisonous species on the Sunshine Coast, there are many good reasons to tolerate and respect the local species of snakes around Hotel Lake as well as in our homes and gardens. Northern rubber boas are known to feed on other snakes, mice, birds, and lizards, as well as worms, slugs, and insects. Garter snakes, hunt insects, some even specialize in daddy long-legs and they help keep pests, such as rats and mice, in check.

Like other wildlife, humans should keep at a distance that doesn't cause discomfort for the animal. Their relative small size means that the taking of photographs will often cause humans to intrude too close. Even our little snakes, if startled or intruded upon, may hiss, coil, puff up, or in rare close situations, bite a person. Unfortunately, these reactive and defensive behaviours by snakes can certainly frighten people who may overreact by striking back, harming or killing the snake.

Armed with the knowledge of the benefits our snakes provide, we have an opportunity to change revulsion and fear into understanding. Biologists will tell you that the best thing that you can do for a snake is leave it alone.

By taking the time to understand these benign and helpful wildlife neighbours, we might enjoy greater harmony and the benefits of living together. Could it be that some of us might eventually come to the same conclusion that many BC farmers have:

“the more snakes on my property, the better”.

A big part of helping snakes is changing our perception from fear and loathing to understanding and tolerance. A wonderful way to begin this process is with our children. The link below will take you to the “Kids Zone” on the BC Reptiles and Amphibians website. With printable colouring sheets, quizzes, projects and even an interactive game, this is a great rainy day resource for children, parents and even grandparents. Make sure you have some crayons handy. Just click on "Kids Zone" below

References

BC Reptiles and Amphibians, excellent info source and maps:

https://bcreptilesandamphibians.trubox.ca/species-reptiles/

Herpetological Society (CHS), extensive information on snakes:

https://canadianherpetology.ca/species/index.html

The Canadian Encyclopedia:

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/snake

Pique News Magazine, article:

https://www.piquenewsmagazine.com/cover-stories/the-long-and-short-of-bcs-snakes-2507892

BC Wildlife Park Kamloops:

https://www.bcwildlife.org/plan/our-wildlifereptilesamphibians.htm

E-Fauna, about garter snakes:

https://linnet.geog.ubc.ca/efauna/Atlas/Atlas.aspx?sciname=Thamnophis sirtalis

BC Magazine:

https://www.bcmag.ca/snakes-you-may-encounter-in-british-columbia/

Bird Watching HQ, article on BC snakes:

https://birdwatchinghq.com/snakes-in-british-columbia/