Tick and Lyme Disease

Any conversation about ticks will generally become re-focused on Lyme disease which is becoming better understood as the number of diagnosed cases increase world wide. Recently, in a conversation with a neighbour who discovered they had a tick bite, the surprise and uncertainty of how to deal with a tick imbedded in their skin was discussed along with concerns that Lyme disease might be involved. Although most of us are aware of ticks and Lyme disease, it may not be the case that we are fully informed and equipped to quickly attend to the removal of the tick and, just as important, what appropriate actions should follow.

Gathering the available science about ticks and one of the diseases they might carry and then sharing that with you, is the goal of this webpage and we acknowledge that we will spend less time explaining the tick and its lifecycle and more time sharing information about Lyme disease which is a growing health concern in Canada.

About Ticks

There are many species of ticks worldwide. Our provincial government states that there are 20 species in British Columbia. According to BC Center for Disease Contorl, Lyme disease, caused by a bacterium called Borrelia burgdorferi is spread by only two species of ticks in BC: Ixodes pacificus and Ixodes angustus, also known as the Western Black-Legged Tick. These are known to bite (or feed-on) humans. The odds that any tick is actually carrying Lyme disease is small, however the consequences of infection can be serious. Before we continue to a full discussion of Lyme disease it is helpful to develop a basic understanding of the life-cycle of the specific ticks on the Sunshine Coast that are capable of infecting humans or pets.

We place the focus on a tick that is prevalent in our midst, the Western Black-legged Tick (Ixodes pacificus). This tick is very common on Vancouver Island, the Gulf Islands, and along the mainland coast as far north as Powell River and also east along the Fraser River to Yale and north to Boston Bar.

Female adult Western Black-legged ticks are red and black and the males are black and slightly smaller. They have a three year life cycle during which they traverse four stages from eggs to larva then nymph and finally becoming adults. At each stage they require a single “blood meal” to survive and progress to the next stage of their lives, as the following CDC graphic illustrates.

The photo below gives a very good sense of the size of these insects. In particular it should be noted that ticks have 8 legs as opposed to most insects with just 6. This can be helpful to anyone who is trying to quickly determine if they are looking a tick or some other insect. Also this photo demonstrates the difficulty of finding a tick on your skin when it is tiny as is the case in the first two stages of life.

These ticks generally live amongst tall grasses and vegetation and prefer a moist warm environment. It is important to know, they do not fly or jump and they do not move far. Because they require a blood-meal at each stage of their lives, finding a “host” for this meal is their primary goal. The blood-meal is required as a source of protein for growth and also for egg development. As the CDC graphic (above) identifies, these ticks can feed from mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians and they do so primarily in the spring as the weather warms. Scientists suggest that many ticks fail to find a blood source and die as a result.

How they hunt for a blood-meal

Ticks utilize several strategies to locate a host for their next blood-meal. Their limited size and mobility leaves just one option; find a suitable location and wait. Ticks seem to be able to identify vantage points beside often-used paths or in long grass or on the lower leaves of shrubs. It is in such locations that they wait patiently for a host.

Ticks are able to detect a mammal’s breath, body odours, body heat, moisture, and vibrations. Some ticks can also sense shadows. Because ticks can’t fly or jump, they simply wait, (questing). To optimize their ability to engage their host, ticks hold onto leaves and grass by their third and fourth pair of legs and hold their front pair of legs outstretched and ready to climb on to the host. When a host brushes the spot where a tick is waiting, it quickly climbs aboard.

Depending on tick species and its stage of life, it may take between10 minutes to 2 hours to commence feeding. Some ticks will quickly find a suitable spot on the host and attach to the skin and start feeding. Other ticks will spend time searching for places on the host where the skin is thinner such as areas on the head around the ear, eyes or nose. Once the location is chosen the tick grasps the skin and cuts into the surface and inserts its feeding tube.

To help keep the tick in its feeding position some ticks secrete an adhesive substance and many incorporate barbs in their feeding tubes to grip the host's skin. The host is unlikely to feel any pain from the tick bite because ticks suppress that reaction with immunosuppressants in their saliva, . So if you can't feel the tick's bite the ways to search for it are to try and visually spot it or to feel for the tick on your skin or to find the bite area after the tick has dropped off.

Undisturbed, a tick will suck blood from the host for several days. After feeding, ticks will drop off the host and find habitat in which to continue to the next stage of their life cycle.

If that were all that there was to say about ticks, we would be finished, but here is the problem:

- If a tick carries a pathogen such as Lyme disease, that bacteria may be transmitted to the host (humans) via the tick's saliva during a lengthy feeding process.

- Conversely, If the host has a blood borne infection, the tick will ingest pathogens with the blood it is sucking and, at its next annual feeding, the infected tick may then transmit the acquired disease to the new host.

Not all ticks carry Lyme disease, but some do. Because infections of this disease are reaching concerning levels in some parts of North America, we shift our attention to Lyme disease and what we can do to protect ourselves. The most useful tool, currently at hand, is information. We continue with the following informative history on the subject of Lyme disease.

A Brief History of Lyme disease

(With thanks to the Bay Area Lyme Foundation, the following brief history of Lyme disease appears below.)

“Ticks and Lyme disease have been around for thousands of years. In fact, a recent autopsy on a 5,300-year-old mummy indicated the presence of the bacteria which causes Lyme disease. A German physician, Alfred Buchwald, first described the chronic skin rash, or erythema migrans, of what is now known to be Lyme disease more than 130 years ago. However, Lyme disease was only recognized in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. And the bacteria that causes it—Borrelia burgdorferi—wasn’t officially classified until 1981.

The 1970s

In the early 1970s a group of children and adults in Lyme, Connecticut, and the surrounding areas were suffering from some puzzling and debilitating health issues. Their symptoms included swollen knees, paralysis, skin rashes, headaches, and severe chronic fatigue. Visits with doctors and hospital stays had become all too common.

These families were left undiagnosed and untreated for years during the 1960s and 70s. If it wasn’t for the persistence of two mothers from this group in Connecticut, Lyme disease might still be little-known even today. These patient advocates began to take notes, conduct their own research, and contact scientists.

The medical establishment began to study the group’s symptoms and looked for several possible causes. Was it germs in the air or water? The children had reported skin rashes followed very quickly by arthritic conditions. And they had all recalled being bitten by a tick in the region of Lyme, Connecticut. Finally, by the mid-70s, researchers began describing the signs and symptoms of this new disease. They called it Lyme, but they still didn’t know what caused it.

The 1980s

In 1981, a scientist who was studying Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (also caused by a tick bite) began to study Lyme disease. This scientist, Willy Burgdorfer, found the connection between the deer tick and the disease. He discovered that a bacterium called a spirochete, carried by ticks, was causing Lyme. The medical community honored Dr. Burgdorfer’s discovery in 1982 by naming the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi.

With extensive backgrounds on Lyme patients and the scientific discoveries that ensued, doctors began to use several antibiotics to treat the disease. This treatment is currently accepted by the medical profession and has been largely successful, especially for those with early-stage Lyme disease. However, there continues to be heavy debate on the long-term use of antibiotics for Lyme that has progressed or appears resistant to a short course of antibiotics.

The 2000s

Since the 1980s, reports of Lyme disease have increased dramatically to the point that the disease has become an important public health problem in many areas of the United States.

In 2012, Lyme disease was included as one of the top ten notifiable diseases by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Today

Lyme disease is one of the fastest-growing vector-borne infections (disease) in the United States with around 500,000 new cases of Lyme disease each year. While it was primarily an East Coast phenomenon in the beginning, it has since been reported in all states except Hawaii. And diagnostic tools are still unreliable—as of yet there is no definitive cure for those with late-stage Lyme.” End of text from Bay Area Lyme Foundation.

What is a Vector-Borne Disease

A vector is a living organism that transmits an infectious agent from an infected animal to a human or another animal. Vectors are frequently arthropods, such as ticks, mosquitoes, flies, fleas and lice etc. Vector-borne diseases are infections transmitted by ticks etc. These arthropod vectors are cold-blooded and thus weather can influence their survival and reproduction rates. Today, Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne disease in the United States.

Reported Cases of Lyme Disease

There are many tick species in North America and many areas where tick populations and the occurrence of Lime disease are prevalent. While areas of the Eastern seaboard in the United States are clearly high risk areas for Lyme disease, areas of southern Ontario, Quebec, Manitoba and especially Nova Scotia have become a growing concern.

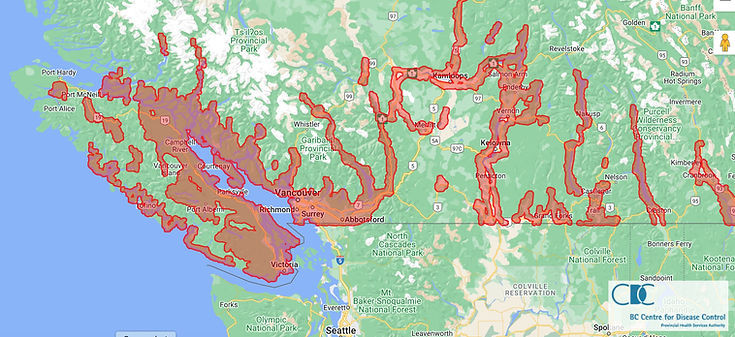

Recently BC CDC published this interactive map to inform the public. The map, which is now available online by clicking here, currently shows people are at greatest risk on the South Coast and in the valleys of the southern Interior. This map is based on ecological niche modelling using observation data from field sampling and clinical submissions, and 10 environmental predictor data layers (vegetation, temperature and precipitation).

When a Western Black-legged Tick attaches to humans, deer, cats and dogs etc, it begins to suck blood, becomes grey in colour and enlarges to a bean-like size.

The bite, while not initially felt by the host, can become irritated or painful much later and may result in a slow-healing ulcer. This tick does not cause paralysis; however, it is known to be capable of carrying and passing on the microorganism (bacteria) responsible for Lyme disease. The organism which causes Lyme Disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, has been found in ticks collected from many areas of B.C., and health authorities now believe that Lyme Disease carrying ticks may be present throughout the province. For more information, go to: B.C. Centre for Disease Control web site.

What should we do?

Understanding ticks and the role they play in transmitting Lyme disease is an important first step. Beyond that, it is not of immediate importance to know which ticks transmit disease and which ticks don’t because, when a tick is discovered attached to skin, it is impossible to deal with such distinctions. What we all need to keep in mind is that while the risk of Lime disease infection is small, every tick bite, when discovered, should be promptly attended to. If the tick is still engaged, carefully remove it, then clean the wound, assess any resulting symptoms and make a decision concerning the need for medical treatment and, in all of this, time is of the essence! It is to these ends that we continue.

All About Removing a Tick

The following is from the British Columbia Center for Disease Control: The most important thing is to make sure that you remove all the tick, including the mouth parts that maybe buried in your skin. Also, do not squeeze the body of the tick when you are removing it. This can force its stomach contents into the wound and increase the chance of infection. If you find a tick:

-

remove the tick yourself;

-

get someone else to remove the tick for you (when you can't reach it or see it clearly); or

-

get your healthcare provider to remove it.

How NOT to Remove a Tick!

Some people think you can remove a tick by covering it with grease, gasoline or some other substance. This does not work! It only increases the chance of you getting an infection. Holding something hot (for example, a match or cigarette) against the tick also does NOT work! Again, this will only increase the chance of an infection or accidentally burning yourself.

When should you remove the tick?

You should only remove the tick yourself, or get a friend or family member to remove it, if the tick is not buried deeply into your skin. The feeding tick's mouth will be under the skin, but the back parts will be sticking out. If the tick has been on your skin for less than two hours, it has probably not had a chance to burrow into your skin. If the tick is just on the surface of your skin, or only biting on to the outside skin layer, you can remove it following the instructions below.

When should you get a doctor to remove the tick?

You should go to your doctor to get the tick removed if it has buried itself deep into your skin. This usually happens if the tick has been on you for several hours, or even a day or two. When a tick has burrowed deep into your skin, it is very hard to remove the tick without leaving some mouth parts behind, which can cause infection.

How to remove a tick

Remove the tick right away (if possible, wear disposable gloves when handling an engorged tick):

-

Use tweezers or forceps to gently get hold of the tick as close to the skin as possible. Don't touch the tick with your hands.

-

Without squeezing the tick, steadily lift it straight off the skin. Avoid jerking it out. Try to make sure that all of the tick is removed.

-

Once the tick has been removed, clean the bite area with soap and water, then disinfect the wound with antiseptic cream.

-

Wash your hands with soap and water.

-

It may be in your best interest to store the tick in a sealed jar. Attach a note of the date and time the tick was removed, the location of the bite on your body and take a close-up photo of the tick after you remove it; all of these may be useful to you and your doctor should you develop chronic symptoms at a later date.

Time is of the Essence

Government of Canada: "You aren’t guaranteed to get the disease. The tick must be attached for 24-36 hours to transmit the disease".

If you have been bitten by a tick or were in a high risk area and are suffering from a rash where you know you were bitten or experiencing a fever, headache, fatigue, muscle paralysis or joint pain, see a health-care provider immediately, the BCCDC says.

Experts say that antibiotics given within 72 hours of removal of a tick can prevent bacteria deposited by a tick from dispersing in the body.

For the estimated 10 percent of people with symptoms that don't respond to a short course of antibiotics, Chronic Lyme symptoms may include fatigue, joint pain, muscle pain, sleep and cognitive issues, heart problems, and more as the poster below illustrates.

Protect yourself, your family and your pets

The risk of suffering a tick bite is greatest in the Spring but can also extend through summer and even into the fall. When you venture outside in tall grass, gardens, parks, or wooded areas:

-

Wear light coloured clothing, long sleeves, pants and closed shoes or boots when walking outdoors in wooded or grassy areas. Tuck your pants into your socks and your shirt into your pants for added protection.

-

Walk on cleared trails.

-

Click on this link to find insect repellents authorized by Health Canada for use on uncovered skin and reapply as frequently as directed on the containers.

-

Check clothing and scalp when leaving an area where ticks may live. Use a mirror or have someone help you check hard-to-see areas and make sure you check your whole body.

-

Shower when you get home to prevent a tick from latching.

-

Regularly check household pets for ticks.

Protect your home

There are some measures you may wish to consider to reduce the risk of being exposed to ticks in the environment or through your pets :

-

Keep the grass cut short.

-

Remove leaf litter and weeds, particularly at the edge of the yard where it can build up.

-

Control rodent activity (e.g. seal stonewalls and openings into the home).

-

Move wood piles and bird feeders away from the home.

-

Try and keep your pets out of the woods.

-

Consider fencing which may exclude deer from entering your property.

-

Trim tree branches to allow for more sunlight into your yard.

-

Create a one metre wood-chip, mulch or gravel border between your lawn and wooded areas/stonewalls.

-

Move swing-sets or playgrounds away from wooded areas.

-

Widen and maintain trails on your property.

Why is it Your Dog Can Get Vaccinated for Lyme But You Cannot?

In 1998, the FDA approved a Lyme vaccine for humans called, LYMErix™, which reportedly reduced new infections in vaccinated adults by nearly 80%; however protection provided by this vaccine was known to decrease over time. Amidst media coverage of anti-vaccine mania and associated fears of vaccine side-effects, sales of the vaccine declined. In 2002, the manufacturer voluntarily withdrew LYMErix™ from the market citing lack of demand.

Since then, humans have not had access to a Lyme vaccination and are therefore increasingly vulnerable to the disease. Subsequently, global rates of Lyme disease cases rose sharply which eventually re-ignited interest and efforts towards the development of a new Lyme vaccine. In August of 2022 phase 3 trials started on a promising new Lyme vaccine identified as “VLA15” which, if successfully released, will likely receive a much higher acceptance rate by the public than two decades ago.

Has Covid Moved Our Attention Away From Lyme Disease?

While researching for this page, it became obvious that in almost every jurisdiction, the collection and publication of Lyme disease data stopped in 2019. While this may be understandable, it must also be very concerning as the confirmed cases of Lyme cases in North America were rising sharply in 2019.

Currently the government of BC, with no data to suggest otherwise, insists that "in BC, less than 1 percent of ticks tested carry the bacteria B. burgdorferi that cause Lyme disease. Although the number of ticks submitted for testing has increased in recent years, the prevalence of B. burgdorferi in ticks has remained consistently low over time." Keep in mind this statement is based on pre 2019 data. Today, it is being postulated that climate warming might encourage tick populations to grow and increase their range. Thus, it is an open question: what are the current tick-bite events and Lyme infection rates in British Columbia. If the citizens of Lyme Connecticut rose up and championed the discovery of Lyme disease, then why can't the citizens of British Columbia now pick up that torch and help to at least gather Tick-bite data.

IMPORTANT UPDATE - MAY 2023 - BABESIOSIS

A new tick-borne disease similar to malaria called babesiosis is being reported in Canada. It is a parasite called babesia that is transmitted primarily through the bite of black-legged ticks and it infects human blood cells.

For some years now this tick-borne parasitic disease has been on the rise in the northeastern United States. Today, the disease babesiosis is considered endemic in a number of those states.

It is believed that climate change and migratory bird flights are resulting in growing numbers of ticks being transported north into Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. These ticks are also bringing babesiosis with them.

Babesiosis is considered a serious disease, especially for elderly or immunosuppressed victims. Complications include renal, liver and heart failure and respiratory distress syndrome.

In response to this emerging threat, the eastern provincial governments have already published information about babesiosis. The province of BC, has not yet done so but will likely review that position as more cases are diagnosed and reported.

What you need to know: Because a tick may carry both Lyme disease and babesiosis a person can be infected by both illnesses. Lyme disease is caused by a bacteria called Borrelia burgdorferi and often presents a large red round or oval rash and treatment and testing can be ordered by doctors. Babesiosis is caused by a tiny parasite called Babesia that infects red blood cells and it does not present a rash. A person who is infected with both illnesses can receive both antibiotic and antimicrobial medication.

The future: Anticipated climate changes are believed to favour ticks and so the “tick season” is likely to grow longer.

What to do: Follow the well published practices for avoiding ticks and do the best you can to be vigilant with personal inspections to detect any bites. If you do find a tick bite follow the well published practices and consider discussing this newly emerging disease “babesiosis” with your doctor.

Information and data are our greatest tools. A simple download of the ETick App onto your smart phone will, allow you to contribute real-time data that will help us understand whats going on around us.

The ETick app is a simple download from Google Play or the App Store on your smart phone. This app permits you to easily report a tick bite and submit details of the location, date, other information and also to easily take a photo of the tick with your smart phone and instantly upload it with your report. Lets be part of the solution!

Library of References

(all underlined links are active)

Government of Canada 2019 report on Lyme disease: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/lyme-disease-surveillance-report-2019.html

CDC - Center for disease control and prevention:

https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/index.html

Government of BC: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/agriculture-seafood/animals-and-crops/plant-health/insects-and-plant-diseases/home-garden/ticks

British Columbia Center for Disease Control: http://www.bccdc.ca/health-info/diseases-conditions/lyme-disease-borrelia-burgdorferi-infection

2011 paper: Lyme disease in British Columbia: Are we really missing an epidemic? Dr.Bonnie Henry and Dr. Muhammad Morshed: https://bcmj.org/articles/lyme-disease-british-columbia-are-we-really-missing-epidemic?utm

North Shore News story: https://www.nsnews.com/local-news/climate-change-is-expanding-the-range-of-these-tick-pathogens-is-bc-next-5384907